Electric cars and trucks account for less than five percent of all vehicles in the U.S. today. But that number is growing, and utility companies, technology firms and EV manufacturers are working hard to prepare for what’s expected to be an explosion in EV demand over the next 10 years. However, according to our research, prompted by discussions we heard at the RoadMap Fourth Conference in Portland, OR, this June, electric vehicle charging stations aren’t reaching every community.

Those areas where few, if any, EV charging stations exist are what we at BlastPoint call Charging Deserts.

Why do they matter?

Charging deserts suggest golden opportunities for public-private partnerships to flourish in the Age of Transportation Electrification. What’s more, charging deserts could serve as hot-spots for driving social, economic, and technological investment where there has, historically, been very little.

After all, as Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities say: “Supporting well-designed transportation infrastructure and public transit can boost the economic prospects of underserved communities by increasing access to jobs and other opportunities.”

Let’s Take a Look at Our Findings.

In BlastPoint’s June 2019 “Electric Vehicle Charging at Commercial Locations” analysis, we report that the Department of Energy currently lists a total of 25,132 public and private EV charging stations nationally, with a total of 74,665 outlets. Of those, 25,089 are in operation and an additional 44 are listed as planned. (Sources: Energy.gov and the Alternative Fuels Data Center)

The Department of Energy also lists nearly 22K chargers as open to the public. The remaining 3,136 are private, accessible only to private fleets or employees of those listed firms.

Further, approximately seven public charging stations exist for every private one.

(Note, this data does not include home charging stations, which is where the majority of EV owners charge their vehicles overnight.)

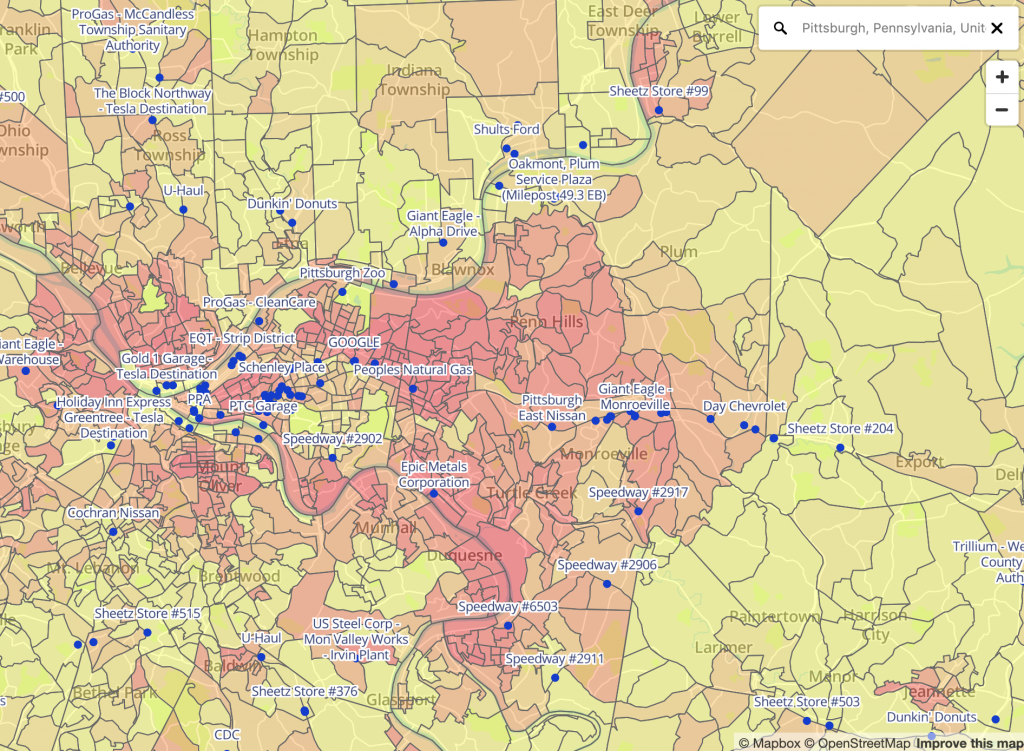

For the purpose of this article, we used the mapping tool in BlastPoint’s platform to create a current (as of this writing) screenshot of all the public and private charging stations in our city, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

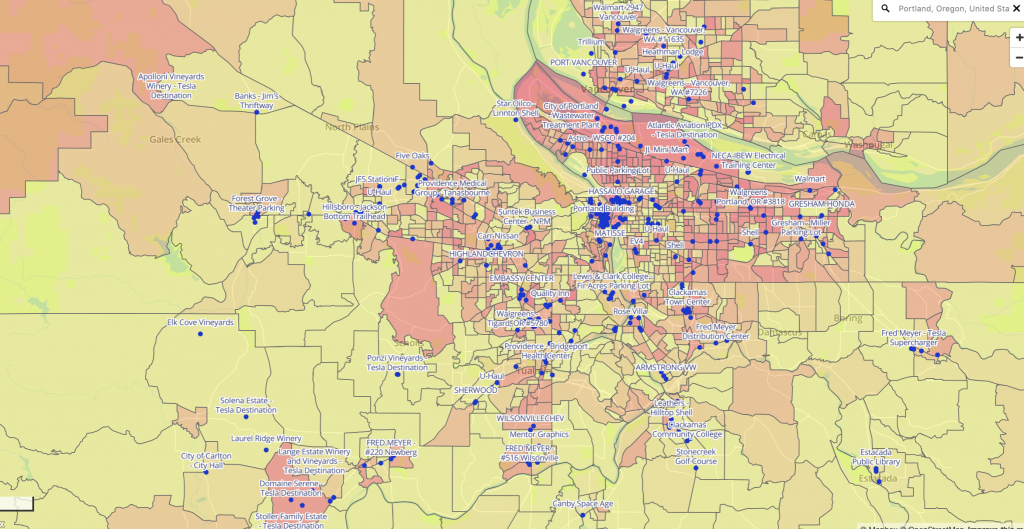

Charging stations are marked as blue dots in the image below. Areas in red denote predominantly low-income, minority neighborhoods, and those in yellow reflect predominantly middle-income Caucasian neighborhoods.

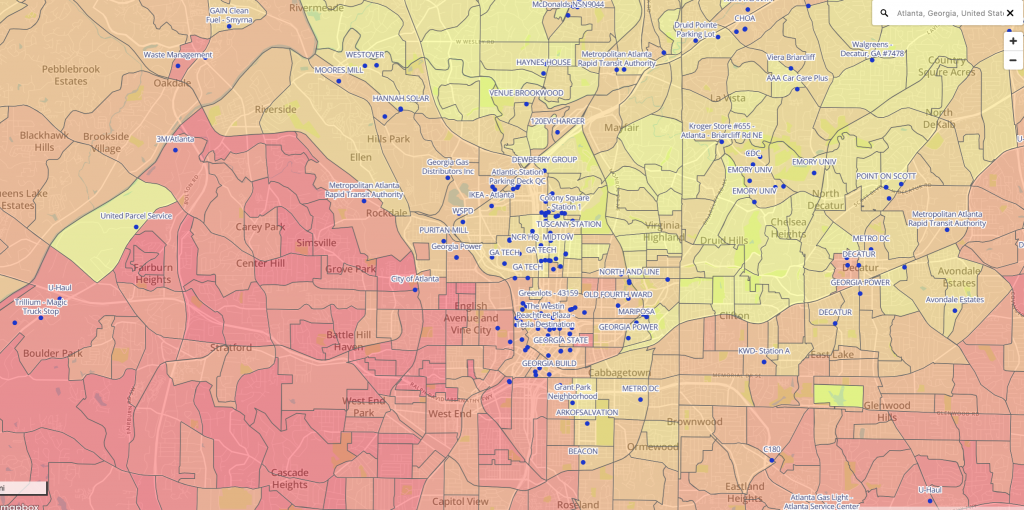

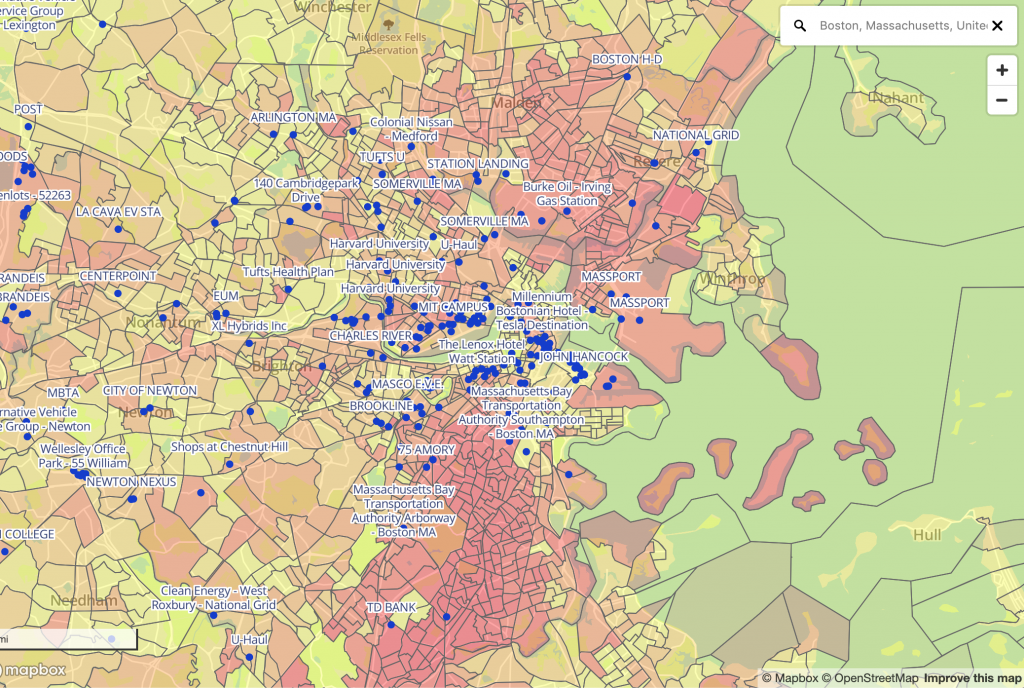

First, we notice that the highest density of EV charging stations occurs in the parking lots of luxury hotels and car dealerships. The same appears to be true for other American cities, like Atlanta, Boston, and Portland, OR, as shown below.

Atlanta:

Boston:

Portland, OR:

Next, we see that gas stations and grocery stores are making EV charging stations available for public use. Parking lots in the suburbs, where commuters leave their cars all day and hop on a train to work also have them. And large-scale employers like universities, as well as commercial truck rental companies offer them. Even brewpubs and B&B’s have them, but these appear to be available only to employees or customers.

All of this is interesting, but it doesn’t explain why EV charging stations exist where they do—or where they don’t.

Possible Explanations

Certainly one reason chargers are where they are is because companies that install them know, thanks to data analytics, where the most EVs have been purchased, and they’ve made fair assumptions about the kinds of places EV owners live, work and hang out.

But it’s more complex than that. Indeed, there are competing forces at play. Natural gas powers 160K vehicles in the U.S. today (compared with 200K+ electric or hybrid-electric), according to the Department of Energy. And many commercial fleets are converting to natural gas rather than choosing electric. Perhaps a lack of outlets in those areas suggests that natural gas is the dominant choice among fleet owners there. (Our mapping research did not look at NGV ownership, however.)

There’s also the classic supply and demand argument over basic economics. Why put more plugs in until we see where more EV sales occur?

Lucky for consumers, EV prices are decreasing. The Nissan Leaf currently costs around $30K. The Chevy Bolt and Hyundai Kona Electric both sell for under $38K, says Will Kaufman at Edmunds.com. This, along with diminishing range anxiety and longer battery life, would explain the growing interest among Americans in EVs. As sales increase, outlet installers can better decide where to go next.

Meanwhile, according to a May 2019 AAA report published on CNBC.com, “Public charging is still limited, especially in the middle of the country, but companies including ChargePoint, EVgo and Electrify America plan to invest billions over the coming decade to fill that gap.”

It’s encouraging to know that private companies are planning expansion projects. But there seems to be a chicken-and-egg scenario developing, i.e., What do we need more of first: electric vehicles themselves, or the infrastructure to support them?

And yet, what stands out to BlastPoint are the echoes we hear from our utility partners: that it’s just plain hard to build partnerships with private business owners who are actually willing to install EVs on their properties.

Perhaps it’s an education issue, a cost barrier, or a what’s-in-it-for-me analysis that needs to be performed before a landowner agrees to install a charging station. Warren Clarke at Smallbizdaily.com outlines four reasons small businesses could benefit from installing one.

But with the necessary technology available, and public utilities prepared to deliver the service, and market interests on the uptick, we still wonder, why are there still so many EV charging deserts?

Looking at where charging stations aren’t, we surmise, may be the key to understanding this issue more holistically.

A Deeper Issue

What our findings reveal is that EV charging deserts exist in neighborhoods that are made up of predominantly low-income minorities, which we know have long experienced a lack of social, technological and economic investment.

In Pittsburgh, that means places like Homewood, Braddock, the Hill District, and others marked in red on our maps above and known for being low-income, predominantly African-American communities.

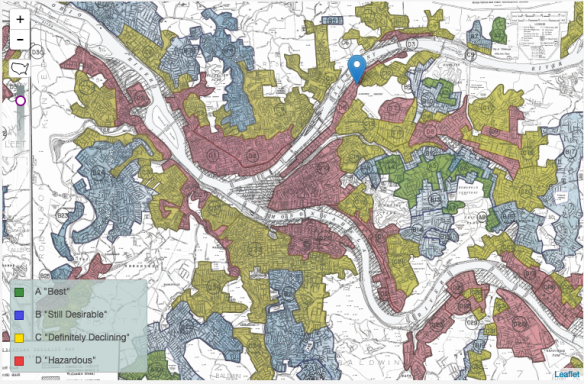

Now, compare BlastPoint’s charging station map of Pittsburgh to the one below, which comes from the University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality project and depicts the discriminatory mortgage-lending practice of redlining that took place in Pittsburgh during the early-to-mid-1900s.

You can’t un-see the similarities.

We believe these insights reveal not just a legacy of inequity, but also an enormous opportunity. One for business owners, technology firms, local governments, manufacturers, community leaders and utility companies to expand consumer EV adoption while simultaneously broadening EV infrastructure.

In the process of doing so, they would also bring investment and innovation to the communities that need them most.