The move in the energy industry away from regarding people as “ratepayers” and toward calling them “customers” has been underway for several years. It marks a meaningful perspective shift in the industry, and it’s significant because it means that energy providers are beginning to think about and treat individual humans in a whole new way.

The term “ratepayer” dates back to at least 1882, when a T.G. Barlow discusses, in the “Gas Journal: Light, Heat, Power, Bye-products, Volume 40,” that ratepayers cede any control they might have otherwise had to the representatives in charge of an organization, and they have no authority in making decisions.

On the contrary, today’s notion of customer service stems from company owners deciding to respond to the unique needs and desires of their consumers, letting them take the lead on what products or services would benefit them.

It’s been a long road getting from there to here. What caused this shift in thinking? Many, many years of trial and error.

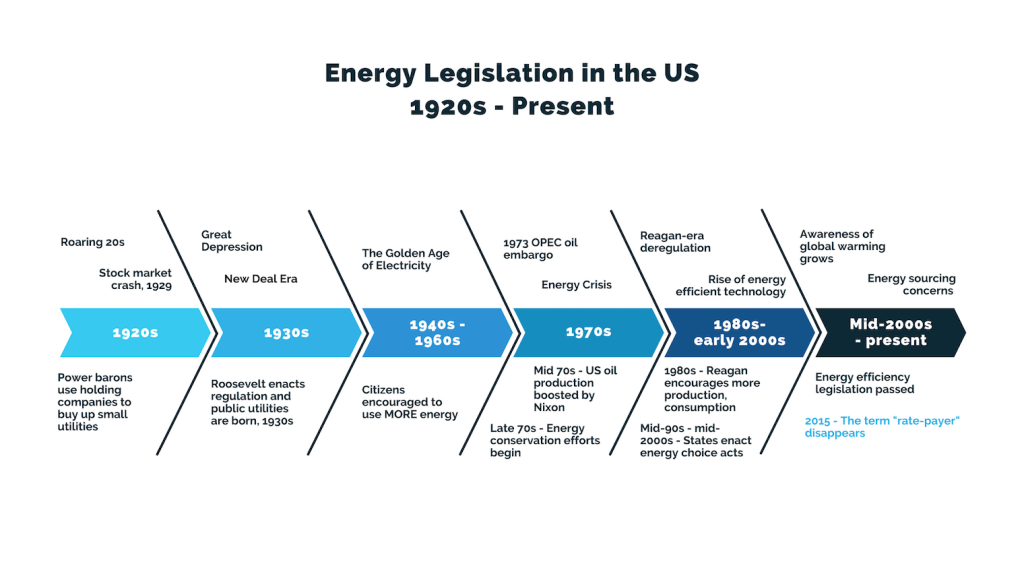

Let’s zoom out and take a waltz through history to fully appreciate this arc of transformation toward a customer-centric focus. The timeline below shows the progression in energy legislation in the U.S. throughout the last century, which, we surmise, has helped to aid this change in philosophy.

Power Barons Out, New Deal In

In the early 1900s, electricity producers sprang up everywhere. With no laws about power generation or transmission in place, it grew to be chaotic. By the 20s, some of the largest energy company leaders (like J.D. Rockefeller) began using private investor holding companies, rather nefariously, to buy up smaller utilities as a way to boost profits. That pyramid model caused major price inflation and it eventually collapsed, although it led the way to energy monopolies controlling the market for many years to come. It’s also partially to blame for the stock market crash of 1929.

Only half of American homes even had electricity at that time, and those homes would have been owned by wealthier families. Even so, it’s hard to imagine the power barons regarding people as individuals with unique preferences and needs.They were, simply, ratepayers.

President Roosevelt called those investor holding companies “evil” and worked fiendishly to allow for publicly-owned utilities instead. He pleaded on behalf of Americans who were struggling to afford heat and light at the hands of the power barons. After a long investigation into utility corruption and fraud, the Federal Power Act of 1935 was passed, giving the Federal Power Commission authority to regulate electricity transmission and rates, keeping prices controlled and the power barons at bay.

Thus ensued an era of heavy regulation and never-before-seen protections for average Americans. This era also gave birth to publicly-traded utilities as well as co-op utilities and others that serviced rural areas which had, until this time, been largely neglected.

Make Way for the Golden Age

The following three decades saw an explosion in energy production of all kinds; what’s now referred to as the Golden Age of Electricity.

After WWII and until the early 1970s, energy prices dropped, production skyrocketed. Power companies and even the government encouraged people to use more energy since more efficient ways of producing and transmitting the stuff were being developed.

(Remember the famous Motel 6 slogan, “We’ll leave the light on for you”? It was launched in 1962. Maybe that’s why we all started leaving our porch lights on overnight…)

1942 began the Manhattan Project, which developed atomic energy for weapons use during WWII. In 1954, the Atomic Energy Act was passed, ending the government monopoly on atomic energy but encouraging the use of it “for peaceful purposes” this time, and also fueling the growth of a private nuclear energy industry.

Slowly, here, we begin to see competition entering the stage, paving the way for consumer energy choice much later down the road. But consumers were still referred to as ratepayers.

The Dawn of Conservation

1973’s OPEC oil embargo, which cut off trade and production of petroleum from Arab nations to the U.S. and others, led to a widespread Energy Crisis, bringing America’s energy-usage bonanza to a grinding halt.

People had to wait in long ration lines at gas stations. Major increases in home heating bills pinched Americans’ pocketbooks. In response, President Nixon boosted U.S. oil production, making up for what we weren’t getting from the Middle East. (You can also thank this era for the much-loathed 55 mile-per-hour highway speed limit, which helped to ease the demand for fuel.) Shortly after that we saw President Ford enact fuel economy standards.

President Carter led the fuel conservation charge in 1977 when, snuggled in one of his signature sweaters, he went on TV to plead for everyone to reduce energy consumption. To some degree, it worked.

Energy saving light bulbs and new thermostats were invented. Electric vehicles saw a rebirth after many decades of lackluster attempts to make them work since the days of Thomas Edison. Retailers began espousing environmental and price concerns to influence the public to cut back on consumption.

Ultimately, The Department of Energy was born to take concentrated control by consolidating a dozen existing agencies. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission also arose during this time of heavy regulation and conservation to monitor the production of oil, natural gas and electricity.

But 1978’s PURPA (Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act) introduced more competition by encouraging non-utility energy production. This allowed for hydroelectricity, geothermal and other power sources to enter the market in a real way.

And it ended promotional rate structures. These had previously encouraged people to increase their energy usage by rewarding them with cheaper prices that kicked in later, only after they’d used up a minimum number of kilowatts.

Overall, these tweaks in the industry turned out to be wins for consumers, though they weren’t necessarily decisions that had been made with individual “customers” in mind.

The Age of De-Regulation

When President Reagan moved into the White House, his first executive order eliminated price controls on oil and natural gas. With the Energy Crisis in the country’s rearview mirror, he saw America as energy-rich, not energy-poor, and viewed regulation as the cause of monopolies.

And so we entered a time of major de-regulation, which is widely credited with spurring innovation, more competition, and the development of privately owned energy production companies.

President Bush Sr. passed the 1992 Energy Policy Act, opening access to transmission networks for non-utility generators and demanding more clean energy production. This trend continued through the 1980s and 90s, as it did in other sectors of the economy. Business leaders touted privatization throughout this time, urging legislators to allow for more choice in the market.

But utility companies still had monopolistic control of the market, and consumers were still only referred to as rate payers. People had only their major regional power companies to do business with, so they had no choice in where their money was going or where their energy was coming from. If your electric company used coal to power your home, that’s what you got. If it used nuclear and hydroelectricity, then so be it. There was no other game in town from which you could choose.

At the same time, utility companies rightly prioritized technology and field work, so they predominantly hired managers with science and technical backgrounds or highly skilled laborers, not marketers or customer outreach departments.

If consumers wanted to communicate with utilities, interactions were typically limited to call center complaints about power outages or overdue bills. Given that behemoth energy companies had a tight hold on the market, there was little need for them to run expensive TV commercials showcasing their attractive products and services. They didn’t need to prove to anyone that they were working hard to please their consumers. And you wouldn’t typically receive information from them in the mail, other than your monthly statement.

The Customer Focus Emerges

But all of that began to change when, in 1996, California and Rhode Island passed legislation giving consumers the right to choose their electricity provider. Soon after, more states followed, and today, over half of U.S. states have some level of deregulated energy choice laws.

Which means many of us can simply break up with our electricity or gas provider if they don’t deliver the level of service we desire. Ouch.

Simultaneously, climate demands have brought energy efficiency to the forefront. Since the early 2000s we’ve seen the birth of energy-saving washing machines, high consumer interest in solar panels, LED light bulbs and more innovations, as well as hybrid, electric and other alternative-fuel vehicles.

Adding even more complexity, the Age of Information (a.k.a. the inter-webs) has transformed the way we communicate. Social media, email marketing, and the gamifying of brand awareness we see in other industries have made customer engagement an elusive beast for many utility companies.

With all this consumer choice available, more energy gadgets to explore, and an ever-changing array of communication channels to use, utility companies are noticing their slim customer service departments struggle.

In response, they’ve had to beef up their outreach efforts, create or at least expand marketing departments, maximize limited resources and develop engagement initiatives from scratch. This hasn’t been an easy lift for most.

In the midst of all this, somewhere in the last few years, the term “ratepayer” officially went the way of the Dodo, according to ICF, a digital consultancy.

At long last, energy providers are finally accepting that they are dealing with customers—customers they need to satisfy or risk losing to the competition.

How can energy companies engage with customers effectively, then? We’ll be addressing this in next week’s post, Unmasking the Modern Energy Consumer.

In the meantime, visit our utilities solutions page to find out how BlastPoint can help your utility understand and engage with the modern energy consumer.